| Edaphosaurus Fossil range: Late Carboniferous – Early Permian | |

|---|---|

Restoration of Edaphosaurus. | |

| Scientific classification

| |

|

Edaphosaurus | |

| |

Edaphosaurs boanerges fossil skeleton on display in Harvard Museum of Natural History, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Lower Permian fossil from Archer County, Texas.

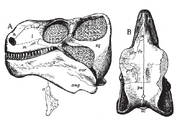

Skull of Edaphosaurus in lateral and dorsal view.

Edaphosaurus was a primitive, herbivorous pelycosaur. Along with the Diadectidae, Edaphosaurus is one of the earliest known plant-eating tetrapods (land-living vertebrates). It had a remarkably small, short and shallow skull, a wide body and thick tail. On its back is a sail, different in shape to that of its contemporary Dimetrodon, the vertebral spines being shorter and heavier and bearing numerous small cross bars.

The earliest known species are known from fragmentary remains of small animals from late Carboniferous. Successive species increased in size during the Early Permian period, until they attained about 3.2 meters in length, as represented by the species Edaphosaurus cruciger and Edaphosaurus pogonias. These large species are distinguished by the cervical and anterior thoracic neural spines bearing large club-like sidebars.

Edaphosaurus pogonias is also the type species, a large Early Permian form whose fossils are known from the Permian red beds of Texas. This genus is also known from the Czech Republic (Nýřany near Plzeň, and Zbýšov near Brno). However it is not known for certain if all these species attributed to this genus actually belong there. The name Naosaurus claviger is given to an earlier smaller species that is usually included under Edaphosaurus.

Etymology[]

The name Edaphosaurus, meant as "pavement lizard",[2] is often translated inaccurately as "earth lizard," "ground lizard," or "foundation lizard" based on other meanings for Greek edaphos such as "soil, earth, ground, land, base" used in Neo-Latin scientific nomenclature (edaphology). However, older names in paleontology such as Edaphodon Buckland, 1838 "pavement tooth" (a fossil fish) match Cope's clearly intended meaning "pavement" for Greek edaphos in reference to the animal's teeth.

Description and Paleobiology[]

Edaphosaurus species measured from 1 m (3 ft) to almost 3.5 m (11 ft) in length and weighed over 300 kilograms (660 lb). This large herbivore had a massive wide body, thick tail, and short limbs which show that it was a slow moving animal. Its broad gut would have allowed it to digest tough, fibrous plant material.

Skull[]

The head of Edaphosaurus was short, relatively broad, triangular in outline, and remarkably small compared to its body size. The deep lower jaw likely had powerful muscles and the marginal teeth along the front and sides of its jaws had serrated tips, helping Edaphosaurus to crop bite-sized pieces from tough terrestrial plants. Back parts of the roof of the mouth and the inside of the lower jaw held dense batteries of peglike teeth, forming a broad crushing and grinding surface on each side above and below. Its jaw movements were propalinal (front to back). Early descriptions suggested that Edaphosaurus fed on invertebrates such as mollusks, which it would have crushed with its tooth plates. However, paleontologists now think that Edaphosaurus ate plants, although tooth-on-tooth wear between its upper and lower tooth plates, indicates only "limited processing of food" [3] compared to other early plant-eaters such as Diadectes, a large non-amniote reptiliomorph (Diadectidae) that lived at the same time. Early members of the Edaphosauridae such as Ianthasaurus lacked tooth plates and ate insects.

Sail[]

The sail along the back of Edaphosaurus was supported by hugely elongated neural spines from neck to lumbar region, connected by tissue in life. When compared with the sail of Dimetrodon, the vertebral spines are shorter and heavier, and bear numerous small crossbars. Edaphosaurus and other members of the Edaphosauridae evolved tall dorsal sails independently of sail-back members of the Sphenacodontidae such as Dimetrodon and Secodontosaurus that lived at the same time, an unusual example of parallel evolution. The function(s) of the sail in both groups is still debated. Researchers have suggested that such sails could have provided camouflage, wind-powered sailing over water, anchoring for extra muscle support and rigidity for the backbone, protection against predator attacks, fat storage areas, body temperature control surfaces, or sexual display and species recognition. The height of the sail, curvature of the spines, and shape of the crossbars are distinct in each of the described species of Edaphosaurus and show a trend for larger and more elaborate (but fewer) projecting processes over time. Romer and Price [4] suggested that the projections on the spines of Edaphosaurus might have been embedded in tissue under the skin and might have supported food-storage or fat similar to the hump of a camel. Bennett [5] argued that the bony projections on Edaphosaurus spines were exposed and could create air turbulence for more efficient cooling over the surface of the sail to regulate body temperature. Recent research [6] that examined the microscopic bone structure of the tall neural spines in edaphosaurids has raised doubts about a thermoregulatory role for the sail and suggests a display function is more plausible.

Discovery and classification[]

See also[]

- Ianthasaurus

- Haptodus

- Sphenacodon

- Platyhystrix - an unrelated animal with a sail on its back

References[]

- Carroll, R. L. (1988), Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution, WH Freeman & Co.

- Colbert, E. H., (1969), Evolution of the Vertebrates, John Wiley & Sons Inc (2nd ed.)

- Romer, A. S., (1947, revised ed. 1966) Vertebrate Paleontology, University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Romer, A. S. and Price, L. I., (1940), Review of the Pelycosauria, Geological Society of American Special Papers, No 28